Alternative Editorial: Competing Long Term Strategies

Mainstream politics threw up two clear examples of its inbuilt self-destruction this week. In the UK, a pair of by-elections overturned long held majorities for the Conservative government, dealing yet another blow to a much-discredited Prime Minister. However, this achievement will be hard to repeat in a General Election.

The first past the post system (FPTP) means the kind of informal collaboration between parties that largely agree with each other (aka the progressive alliance) will be suppressed, in favour of winner-takes-all competition. Boris Johnson knows that even if most voters disapprove of him, the wildly disproportional UK electoral system can still deliver to give his party full control of government.

In the US, with a similar system, the situation has recently become very grave. Despite 61% of citizens believing that women should have the right to govern their own bodies, a similar FPTP system has allowed the Republican Party over 50 years, to slowly gain control of the Supreme Court that takes those rights away. Despite 90 % of people demanding to have less access to firearms, the only piece of legislation passed on gun control this year, is to give them more.

More and more observers are tracing back to when such long-term plans were incepted. How President Nixon, for example, set the pattern by appointing four supreme court judges during his short time at the White House.

More mundanely, when we dissolve diversity into binary opposition – Left v Right, Traditionalist v Progressive – one half of the country is completely invested in the failure of the other half. When you add low voter turnout to that picture - or systematic voter suppression - it becomes very easy for anyone with a plan to take control.

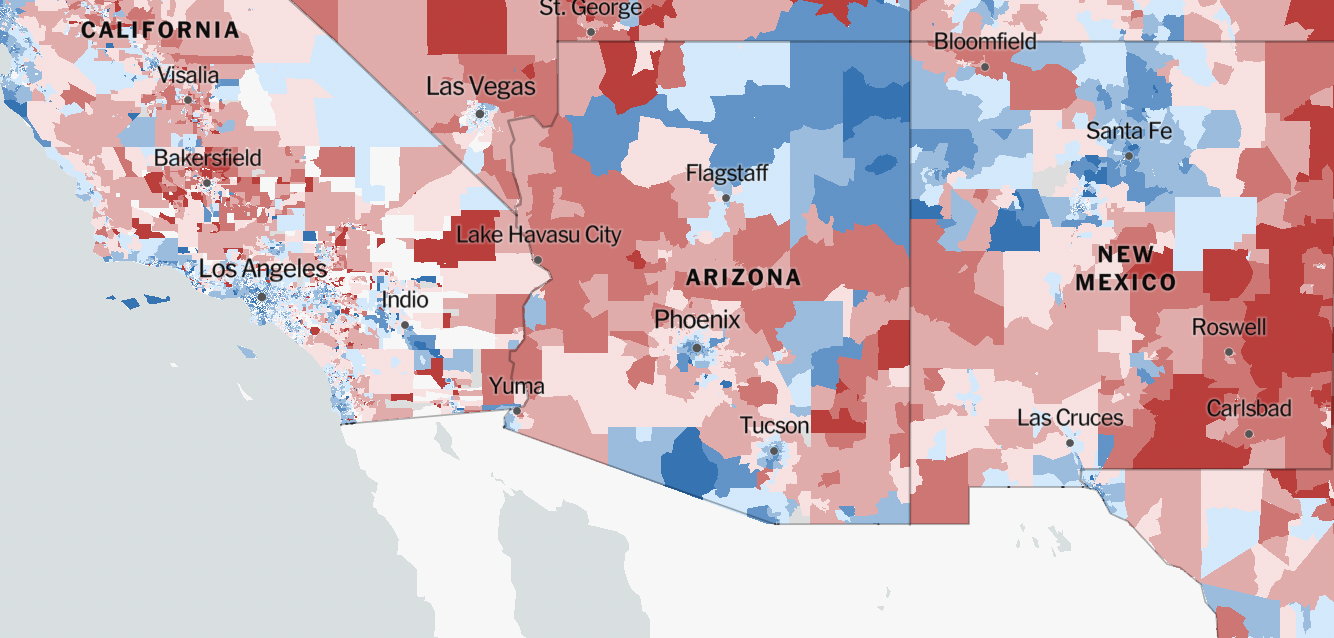

Even so, as our blog immediately after the last US Elections showed, the stats steadily display a much more complex picture of the ‘divided nation’ than the media tends to report. Each state has a mixture of red and blue voters, often in the predictable pattern of Republicans in more remote habitats and Democrats in built-up areas. The UK too shows a similar pattern of deeply rural and suburban voters voting differently from those in cities.

Rather than polarise these sections of voters, as political parties do, there is always the possibility – not easy - of bringing them into a better relationship. How do you find ways for people across a region, or from the outer edges of a city to the better-connected parts, to come to build trust between them? The Alternative’s early ‘collaboratories’ imagined this simply as a three-step process – Friendly, Futuring and Initiating. Today this design has elongated to include a pre-Friendly sense-making process (such as the pol.is experiments now trialling in Wandsworth or Cynefin’s Sensemaker, and community imagining (such as Civic Square’s Re_ Festival or The Onion Collective’s work with Moral Imaginations.

In a recent play-space we occupied with the Presencing Institute, five putative CANs also went through a U-Lab process. The aim was to pay close attention to the wider social dynamics always present in the coming together of a diverse and complex community. How the individual and collective experiences of the citizens and the place – whether traumatic or enabling - can either limit or massively expand the potential of that community.

The most interesting part was simultaneously joining in the global U-lab process, enabling similar social experiments in 90 countries to hear from each other. While on the one hand, each geographical location had its own distinct story to tell, it was apparent that were all affected by a shared wider reality too. Not only the scientific facts of climate breakdown and increasing inequality, but the global impact of the war in Ukraine.

With the availability of CNN or BBC and global access to English speaking news, the growing questioning of long dominant narratives - from the American Dream to European colonialism – is beginning to empower those who exist outwith that framework. If, until even recently, America has exerted an unrivalled soft power – the ability to attract every other country into its sphere of influence – today that is waning. Particularly post-Covid, those countries that handled the pandemic more effectively are re-grouping themselves – South Korea, Japan, Singapore – and developing new narratives about the future.

What is fascinating is that, at the level of grassroots communities coming together – at least amongst U-labbers – there is a common appreciation of the necessity of moving independently of their respective governments. That coming together across the traditional political divides, they believe, is in the interest of people and planet everywhere. What’s more, particularly (but not exclusively) in the socio-spiritual space that the Presencing Institute offers, there is a strong sense that this kind of life-centred activity - connected, regenerative, caring – plays a novel role. While on the one hand it draws on ancient, indigenous wisdom, it also acknowledges that we have never before had the kind of technological capability to share such learning, at this scale.

Whoa, we hear you say: are you claiming that we should now trust the tech revolution? Aren’t Facebook, Google, Twitter the very architects of the polarisation and gross monetisation of human vulnerability everywhere - which we started out complaining about?

Yes – but what is being described here is much more than these corporate operations. The moving into relationship of people in the places they live, all over the globe, is the socio-political innovation we seek. Yet their conscious use of technology to connect beyond their own location to others, showing similar patterns of emergence, is what will make the difference we need. We only have a short time to counter the implosion of the old system.

This partnership between the cold data of digital systems with what Nora Bateson would describe as the warm data of idiosyncratic emergence at the community level, is core to what we describe as fractal scaling. Instead of centralised scaling – naming a prototype and dropping it into towns and cities top down – this is the recognition of patterns of organisation occurring from bottom up, enhanced by digital technology.

To some extent, they depend on the possibility of viral connectivity to be able to move quickly. However, as all those involved in the steady building of CANs – from neighbourhoods to municipalities to bioregions – will testify, it could go faster than it is going right now. The work of bringing together complex communities is demanding: burn out is a regular feature of those fully immersed, seven days a week. And like women’s work over the centuries, it’s more likely than not to be unpaid, voluntary labour.

What’s needed now is a better system of communication between the CANs that can enable fast access to each other’s learning, tools and tricks. While this exists in pockets such as the global commons designed by Michel Bauwens and the peer-to-peer movement, we are overdue a platform that connects that to all the other CANs movements globally.

Of course, any one of us could map the current situation, show their commonality and make their ‘open source’ assets more visible to each other. But the more ambitious thing would be to open up channels of regular communication between them, so that rich relationships can form. This system is a step further than the kinds of networks often cited when talking about the growth of a sector.

More than offering a theory of change, a relational system is the coming alive of everything each element stands for – more than the sum of those parts. For all readers who spend regular time in Zoom rooms, patiently forging new groups and narratives, you’ll know what can happen. Pennies drop, realisation occurs, and new sensibilities arise much faster than can be managed by a bureaucrat. A one-hour online meeting between similar operations on different sides of the world can be game-changing for all parties. Our own fortnightly meetings of co-creators at Alternative Global are testament to this.

Writ large, this kind of cosmolocal inter-activity—holding within it the coming together of diverse communities—is an alternative strategy for reshaping the socio-economic-political system. We, the people, do not have to stay in thrall to the collapse of the old. We can shift our gaze and pay our precious attention elsewhere and commit to our own long-term plan.