Peer-Designing, Open Blueprints and Maker Machines: how to put design and production in the hands of people and communities

Product range from Precious Plastic

We are excited to read Selçuk Balamir’s Postcapitalist Design thesis - as much for the series of concrete, community-usable ideas that come out of it, as for the overall big picture of “what comes after capitalism” that it invokes. We’ll concentrate on the former here.

BTW, Selçuk has a fascinating activist background [see here], involved in major creative protests and building two concrete, commons-based communities in Amsterdam - so his proposals have real experience and practice behind them

“Postcapitalist design” is essentially about creating situations where we are not passive consumers of glossy objects and services, designed in sealed boxes by far-off corporations. Instead, we have an active relationship with these objects and services, co-designing and co-creating them, in a “commoning” rather than “commercial” environment. (Those who know our work in imagining and fomenting CANs (citizen action networks) might understand our interest in this).

Selçuk breaks down the new components of this practice into three chunks: Peer-Designing (becoming ‘Designer-Commoners’), Open Blueprints (Instituting ‘the Wikipedia of Things’), and Maker Machines (Providing everything for everyone). Here’s a summary of the whole paper, but we’ll identify the highlights below:

Peer-Designing

Peer-designers are those whose creativity and innovation overflows the commercial business they’re involved in, compelling them to set up platforms and networks whereby that creativity can both be shared with other peers, and enrich a public commons. Yet while there are many of these networks sprouting, there’s a difference to be pointed out, says Selçuk:

A simplified distinction could be made between current peer-designers and future designer-commoners;

Improvised vacuum, by Jesse Howard for Open Structures

the former are unable to reproduce themselves fully, and are therefore predominantly precarious, involved on an ad-hoc and voluntary basis

whereas the latter have established themselves as providers of indispensable social functions, carrying more responsibility and intentionality.

We’re genuinely interested in the “designer-commoners” at A/UK. What are the design potentials coming from the activities of mutual aid networks, food coops, community-wealth building schemes?

Selçuk identifies another piece of equipment needed:

Open Blueprints

The subtitle “a Wikipedia of Things” makes it clear what the object is: some kind of digital and social repository where designs can be responsibly deposited, and responsibly reused, in a common way.

There’s much discussion in the paper of Open Desk (here) and Wikihouse (here) as example of how these open blueprints can be used. Superficially, as an add-on to existing commercial practices, it could easily become an exploitation of the overflow of creativity mentioned earlier.

Yet, if part of a wider and bolder vision for mutual producing, in which the livelihoods of makers are a concern - that is, Open Blueprints supporting Open Making - it could be revolutionary. What’s needed is:

a universal library in which to pool open blueprints;

established norms and tools to maintain and govern this commonwealth of design knowledge;

and a social and logistical infrastructure that supports the livelihoods of all the contributors.

This triad is very much in line with the following note of caution: “the expectation that one can change society merely by producing open code and design, while remaining subservient to capital, is a dangerous pipe dream” (Bauwens and Kostakis).

In other words, casually open sourcing designs does not lead to a commons-based economy, as the real work comes in the designing and growing of the institutions that infuse them with purpose and value.

Peer-designers drawing on open blueprints then need…

Maker Machines

There is a decisive line in this section:

Without identifying the role of technology in achieving social and ecological benefits, there would seem to be little distinction between self-imposed frugality and systematically enforced austerity.

This speaks to our own anxiety in A/UK - that radical technology’s powers can be harnessed to the benefit of communities, instead of those communities resisting them as corrupting or enslaving. Selçuk suggests that we need a “counter-industrial”, not a post-industrial vision - “counter-industrial not only means (anti-)opposition, but also retaliation and rivalry, or doing better than the industries in order to overcome them”.

He proposes that there are a “great range of cultural transformations prefigured in the steel, solder and circuits of mundane machinery.” What if we could “reverse the sophisticated austerity of the commodity-machine with a simpler postcapitalist abundance”? An intriguing vision.

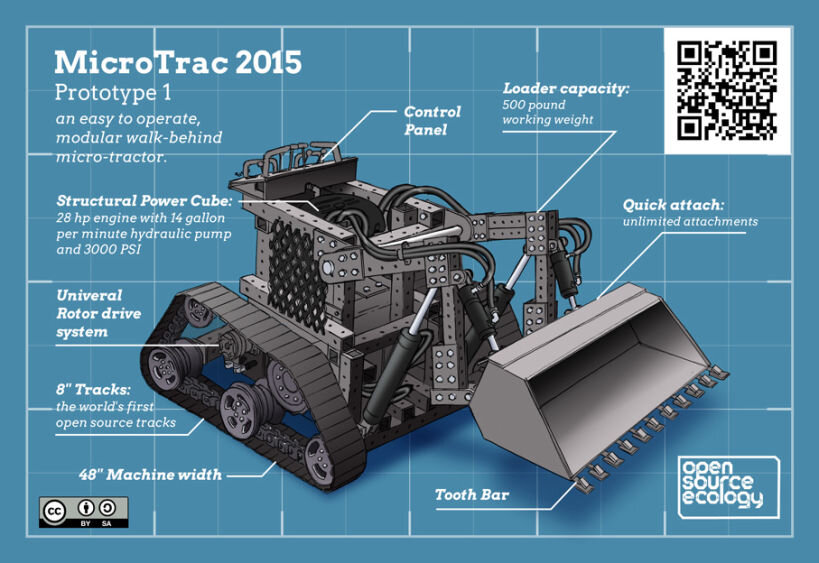

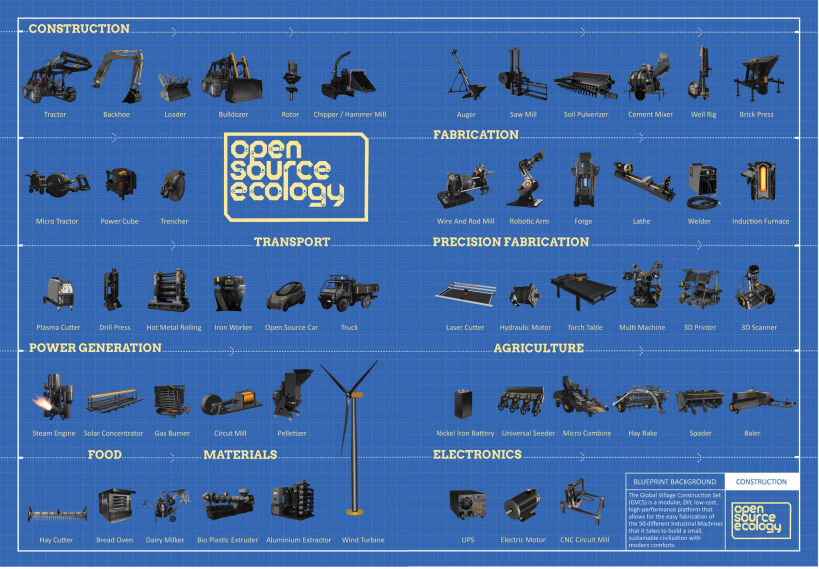

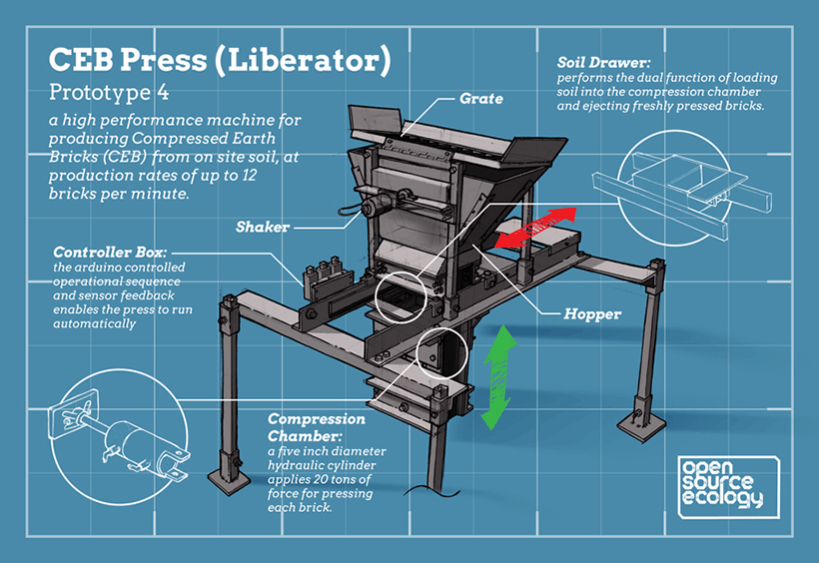

Selçuk then runs through a series of case studies to prove this counter-industrial potential, including Open Source Ecology, the Factor E Farm, Global Village, and Precious Plastic.

We’ll conclude these brief extractions from a massively rich paper with these summary paragraphs:

In this study, I have analysed how commoning takes place in design practices. Commoning in design covers a vast and complex field of collaborative practices and collective actions that create shared value, uphold institutional arrangements, and provide a simple abundance of sustainable goods.

Commoning democratises design – not because everybody magically becomes a designer overnight, but because it generates livelihoods for makers everywhere.

Commoning enables people to produce quality goods and work fair jobs, to participate in localising, improving, and adapting products to suit an enormous array of needs, possibilities, and desires.

When considered as instances of commoning, these practices stand out as early emblematic pioneers in postcapitalist design. Together, they constitute an ecology of subjectivities, practices, and discourses.

In every case study I analysed, this strategy of commoning is riven by a productive tension between speculative discourses and prefigurative practices. Through this tension, these practices negotiate creative work and political action.