Using the net not just to reduce polarisation, but also to make new supportive spaces: danah boyd and the Study Web

From Every

In our investigations with peers into what an Alternative Media System would look like (ongoing), we’re taking on board documentary maker Adam Curtis’ recent comments - that it’s in our power to design a web that isn't just an exploiter of our attention and passions, and return it consciously to its earlier promise as a democratic tool.

Here’s two pieces that first show how to start this new design, and second that can see it arise even from current equipment and services.

danah boyd on knitting a healthy social fabric

danah boyd (that’s how she spells it) is an esteemed researcher for Microsoft on the social impacts of technology, In this address on May 18, 2021 to Educause’s annual conference, boyd addresses “what we can and should do to knit a healthy social fabric”. The whole talk is hugely worth engaging with, but her intro is a great lead in:

Many people see the roots of polarization and hate in the information ecosystem in which we are embedded. This leads us to conversations about disinformation, platform power, and the politics of speech.

I see the roots differently. In my mind, polarization and hate are expressions of a fractured social graph - that is, of people not being connected to one another in meaningful and deep ways. Divisions in social networks (connections between people, not technologies) have serious consequences.

The social graph of society is civic infrastructure, but too few people really understand how this needs to be nurtured and maintained.

Plenty of people do this by feel. You can see this in the military and in higher education. You can see this when organizations build mentorship programs and when social workers build plans to help people leave “the life.”]

But you can also see how people manipulate the social graph in order to aid and abet a range of political, ideological, and economic agendas. There is nothing “neutral” about the social fabric of society. Ignoring it doesn’t mean that it will be healthy, but it does create a vulnerability that can be abused.

… We cannot sustain democracy or work towards a more equitable society without grappling with the social network of our various countries. There are many things that we can and should be doing in every part of society — including business, government, and civil society — so I hope you’ll read this talk and start imagining interventions that you can do to make the world a healthier place.

The talk is here. There’s a fascinating section where boyd talks about “familiar strangers”:

Stanley Milgram was a psychologist best known for his “obedience to authority” experiments, but he also conducted a series of studies of “familiar strangers.”

Consider someone you see ritualistically but never really talk with. The commuter who is on your train every day, for example. If you run into that person in a different context, you are more likely to say hello and strike up a conversation. If you are really far from your comfort zone, you almost certainly will bond at least for a moment.

Many students are familiar strangers to one another. If you take them out of their context and place them into an entirely different one, they are more likely to bond. They are even more likely to bond when the encounters keep happening.

Many people have long wondered why the Grateful Dead succeeded in creating a world of Deadheads. It turns out that’s because the people who allocated tickets understood familiar strangers. If you bought a ticket for a Grateful Dead show in Miami, they kept a record of who you were seated near.

Then, if you bought a ticket for the Nashville show, they’d seat you near someone who was near you in Miami. By the time you encountered the same people in your section of the show in Chicago, you’d be talking to them.

You can strategically nudge people to connect by creating the conditions where they keep encountering each other. Even if the relationship does not persist when they return to their normal context, they’ll have a mutual sense of appreciation for one another. This is the power of taking networks seriously.

And because of technology, you can see how things evolve over time. These are but a few potential ideas for how you as educators and tool makers can contribute to the intentional nurturing of the social fabric.

But what I want you to see is that this is doable. You can be as intentional about knitting the social graph as you are about your pedagogy. And both are key to empowering your students.

Currently, you nudge all the time without realizing it. But let me be clear — you don’t have to do this without your students knowing that this is what’s happening. Now that you understand that this is happening, you can make it a conscientious part of your own practice.

And you can teach your students how to see networks and understand networks. You encourage students to make new connections for future job opportunities, but you can also invite them to really evaluate their network and think about how to be more reflexive about what relationships they are nurturing.

You can work with students to creatively think about how to build connections for the health of the broader social fabric. After all, most students aren’t looking to undermine democracy. They don’t want to be a pawn in someone else’s plan. So empower them to be strategic in the network-making project.

A safe harbour in a fragmented time: the emergence of the Study Web

And here’s a great, concrete example of how supportive networks can be actively constructed, where there’s a driving need. And certainly, in pandemic conditions, the need for support to be an online learner is obvious. This original article from Every, written by Fadeke Adegbuyi describes a rich culture that has opened up around this need:

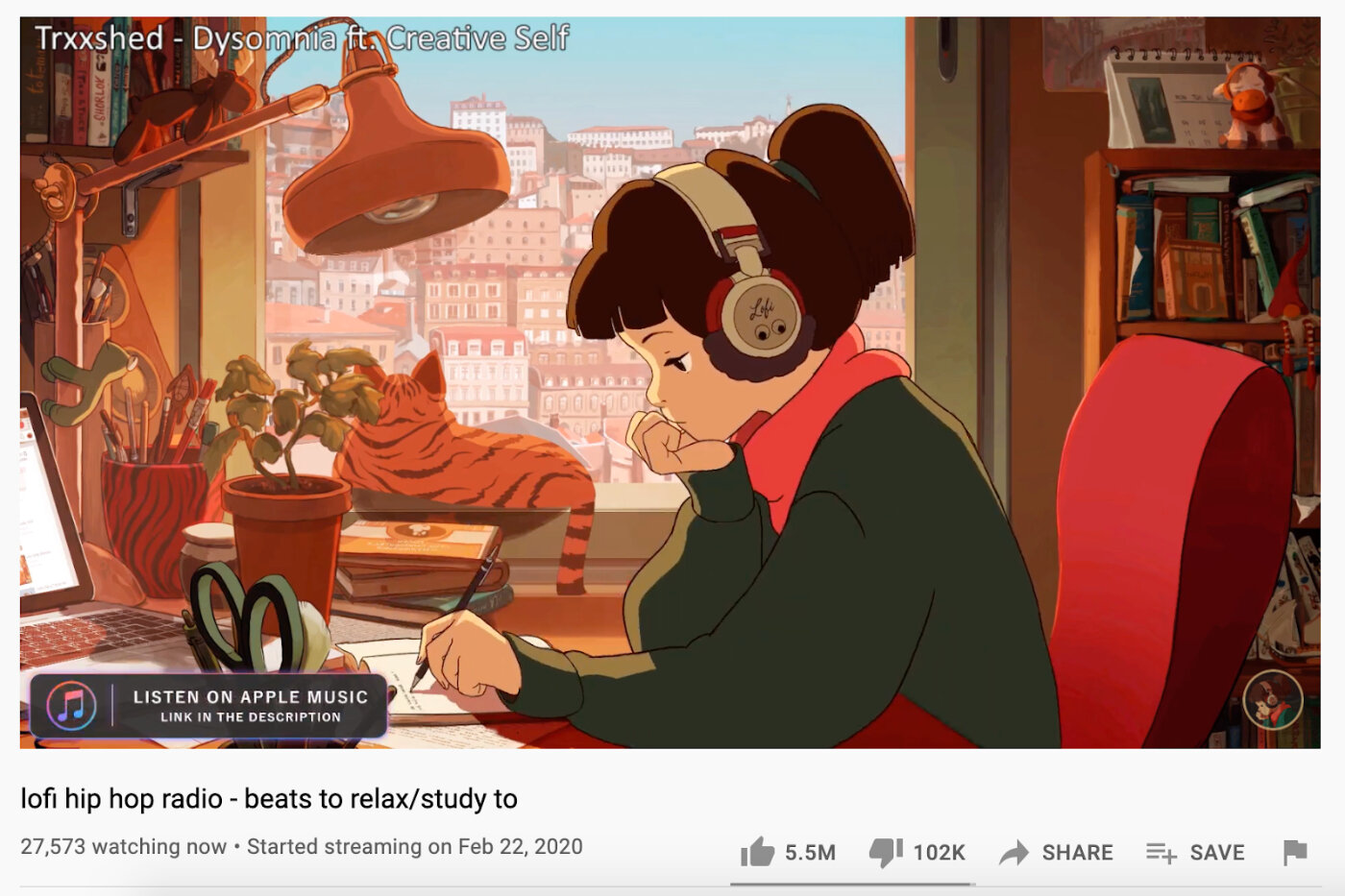

Study Web is a vast, interconnected network of study-focused content and gathering spaces for students that spans platforms, disciplines, age groups, and countries. Students seeking motivation, inspiration, focus, and support watch livestreams of a real person at their desk, studying; videos in the Study With Me genre are simultaneously streamed by thousands of students.

Or they join Discord communities, where they search for “study buddies,” share studying goals, and compete—by studying—for virtual rewards. On Twitter, they swap study tips and seek out study “moots,” or mutuals, under the hashtag #StudyTwit.

…The Study Web is a constellation of digital spaces and online communities—across YouTube, TikTok, Reddit, Discord, and Twitter—largely built by students for students. Videos under the #StudyTok hashtag have been viewed over half a billion times. One Discord server, Study Together, has over 120 thousand members.

Study Web extends far past study groups composed of classmates, institution specific associations, or poorly designed retro forums discussing entrance requirements for professional programs. It includes but transcends Studyblrs on Tumblr that emerged in 2014 and eclipses various Reddit and Facebook study groups or inspirational images shared across Pinterest and Instagram.

Populated mostly by Gen Z and the youngest of millennials, Study Web is the internet most of us don’t see, and it’s become a lifeline for students from junior high to college.

Much of Study Web parallels more adult and professional spaces that have emerged in the last decade—revered influencers, a bend towards materialism, and inspiration over analysis. But it’s also a reflection of the realities of young people today that most of us miss.

Why are millions of students from around the world spending countless hours online, tangled in the Study Web of their own design?

In the highly-pressurized pursuit of the academic goals they’ve been told will help them succeed, students venture into Study Web to feel less alone; assuaging anxiety with inspiration, pursuing perfect grades through para-social productivity, and quelling fears about the future with cyber friends.

As Zoom school has left young people even more desperate for connection and support, they’re turning to Study Web—post-to-post, DM-to-DM, and webcam-to-webcam—to find it.

From Every

After a tour de force of ethnographic study of these communities, Adegbuyi concludes:

…Study Web is the space students have constructed for themselves in response to the irl system that just isn’t working. Unable to find a place or person to turn to with their academic and career anxieties, they find internet strangers—strange kin—to speak to, or simply share the same space with, online.

Lacking the intrinsic inspiration to study for hours each day, online advice and group accountability provide a solution. Feeling isolated, virtual study partners create a sense of fellowship. On Study Web, while stressed, students have accepted their lot—they’re not investigating the rightness or wrongness of the pressurized environment of the Gen Z student or asking whether college is worth it at all.

12-hour Study With Me videos are seen as something to aspire to rather than rebel from. Students accept the premise that school and studying are non-negotiables. Where they come from, where they live, their beliefs and value systems are not barriers to community-building; they suffer in common.

However superficial, with its built-to-inspire content and Amazon Prime finds, Study Web speaks to the experience of being a student in 2021, anywhere in the world. Study Web offers a respite, acknowledging the pains that can arise as a student and trying to make the best of it together.

Between the soft lighting, the music, and a collective camaraderie, Study Web feels like a safe internet harbor for a generation that’s found itself adrift.