For "joie de vivre", try "joie de faire": how happy, purposeful crafting, for adults and pupils, can ground us in pandemic times

In 2017, we brought the idea of craftivism to this website, with this blurb:

For the introverts among us, traditional forms activism like marches, protests and door-to-door canvassing can be intimidating and stressful. Take it from Sarah Corbett, a former professional campaigner and self-proclaimed introvert. She introduces us to "craftivism," a quieter form of activism that uses handicrafts as a way to get people to slow down and think deeply about the issues they're facing, all while engaging the public more gently. Who says an embroidered handkerchief can't change the world?

Three years on, Sarah’s Craftivist Collective organisation is going from strength to strength - here’s her script for a Radio Four ‘Four Thought’ programme from just a few weeks ago.

What’s fascinating about Sarah’s approach is that it combines a deep love of craft, a keen activist commitment, but also a grounding in some interesting psychological research.

See this fascinating story from the R4 script, on craftivism delivering very effective “good surprises”:

Another way craft can be useful is to help activists become critical friends rather than aggressive enemies.

If we feel attacked or judged, our instinct for survival takes over: we get defensive, we listen less and can become even more stuck in our ways. So, when it comes to protesting, we need to be careful about how we interact with power-holders if we want them to engage with our concerns and to be part of creating the solution.

That’s why one of our strategies is to hand-craft small, bespoke gifts for decision-makers. Genuine, respectful gifts. For example, the Head of a campaign organisation came to tell me that for 3 years they had tried, unsuccessfully to gain a meeting with the CEO of a major retail company, to discuss becoming a Living Wage employer, and did I have any new campaign tactics they could try. I thought hmmm: “Who does the CEO of the business have to listen to?” The Answer? His 13 other board members.

So I recruited 14 craftivists who fitted the core-customer demographic of the business and delegated them a board member each. I asked them to research their board member’s personality, passions and even what colours they wear the most.

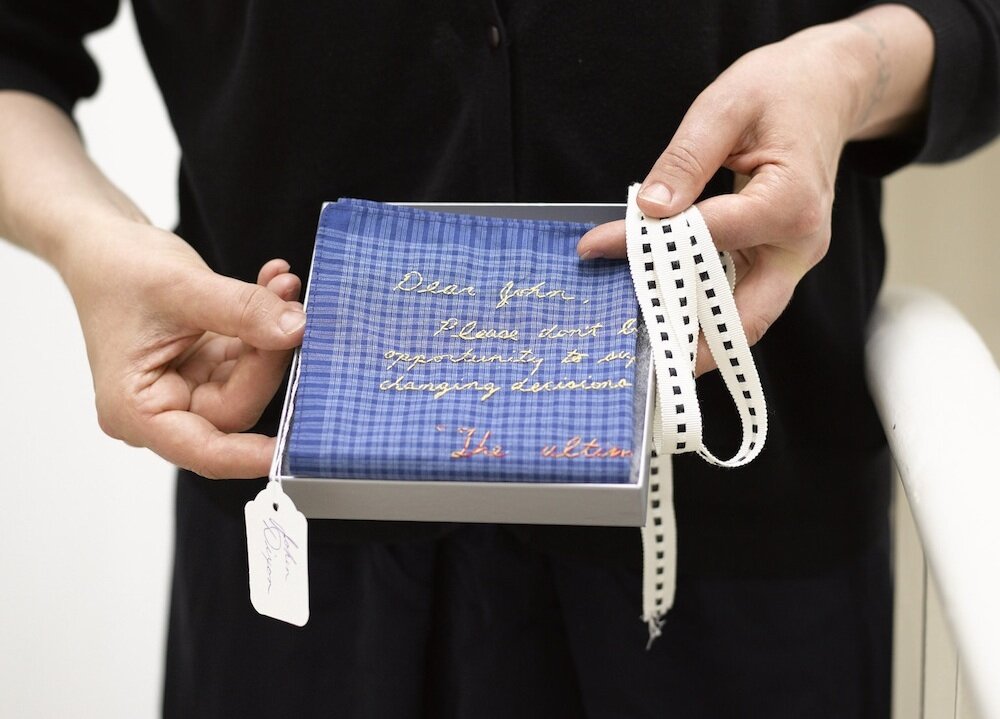

And then, find an encouraging quote about being a positive changemaker, from someone the board member would admire and stitch it on a handkerchief that I had bought from the company encouraging them not to ‘blow it’ but to use their power to create a positive difference through their role.

We then hand-wrote letters to go with the gift to say how we loved the company’s products and that we were saddened to hear that they don’t pay the Living Wage, because that would help their staff not to struggle financially or have to get second jobs, but also it makes business sense to be a Living Wage Employer.

We bought shares and went to the AGM as shareholders. We wrapped up our hankies and letters in boxes with ribbon, to hand over one-to-one with a smile and humility. Within the next few months we had a few meetings and respectful correspondence, and before the following AGM the Chair of the Board announced a pay increase for 50,000 staff in line with the real Living Wage. We went to that AGM, this time to thank them and encourage them to become accredited Living Wage Employers.

In the break, many of the board members searched for their craftivist to thank them personally for their gift. One hanky was donated to the company’s permanent archive to represent a part of the change in the company’s history! One board member told us that they had to explain to their children what the living wage was after they had seen the hanky.

The Chair of the Board told me quietly that it was the most powerful campaign they had ever experienced because it was so unusual, so respectful and we had a robust argument they couldn’t dismiss.

Neuroscientists call this a ‘good surprise’. A lot of activism is often a ‘bad surprise’ – getting a milkshake thrown at you or a loud demonstration pop up outside your office. These often cause ‘fight or flight’ responses. Good surprises create dopamine, the feel-good neurotransmitter, in the brain of the decision-maker, which means they are more likely to engage with the activist in the moment and in the future.

“What we make, we know. This is visceral”

Actually, it was the following article that brought us back to craftivism - which is this short essay from the excellent new Psyche website, “Handcraft lessons belong in a radical school curriculum”. It’s written by Hinda Mandell, an associate professor in the School of Communication at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. Her books include Crafting Democracy: Fiber Arts and Activism (2019), co-authored with Juilee Decker; and Crafting Dissent: Handicraft as Protest from the American Revolution to the Pussyhats (2019).

In the following extracts, Hinda begins by recalling a phrase that some of us remember all too well from our far-off schooldays:

What if bringing back home economics were a radical – not retrograde – act? And I’m not talking about a one-time course, introduced in middle school, when young people (deep into an adolescent surge of hormones) have already internalised gender norms dictating who should be mending socks at the kitchen table versus who should be welding metal in the garage.

Of course, we’d have to axe the name – a throwback to the 1950s, and redolent not just of gendered segregation but of heteronormative training and aspirational class-climbing. We’d also have to grade the offer if we’re to embrace teaching preschoolers to make tote bags out of dish towels and high-schoolers how to knit socks to the exact measurement of their feet.

In short, I’m talking about establishing handcraft courses that are in regular rotation throughout the school year, just like music, art and physical education.

Through ‘handcraft’ courses, students learn by doing, making, drafting and constructing – the kind of manual work that has little need of specialised or costly equipment. Like the re-learning of a lost tongue, this is a form of reclamation clearly tied to the communal wellbeing of society, to stitching empathy and resilience to the shared knowledge and lineaments of a heritage…

We – the public – now viscerally intuit that ‘domestic skills’ possess relevance and necessity beyond the home. Skills deemed run-of-the-mill as little as two generations ago – such as operating a sewing machine, planning and growing a garden, canning seasonal foods – now carry vital survivalist import. Plus, they are work that involves cognitive and physical labour – made all the more meaningful via generational knowledge transmission.

What is produced by hand is linked to familial, public, mental and physical health, and a sense of purpose and self-sufficiency. Can’t get sliced bread? Then make it. No access to bleach or rubbing alcohol? Let’s clean with baking soda and vinegar. Let us husband disappearing dollars by darning old clothes and refashioning new ones from existing fabrics in our drawers.

Home economics was basically a life hack, before ‘hack’ became a fashionable word for making lives easier in a capitalistic system that leaves people gasping for air.

What we make, we know. This is visceral. And what we know influences our values, frameworks and economies. Philosophers since Plato have argued that the physical construction of fabric – for instance – affects the scaffolding of knowledge-building, as well as our actual built environments.

From Psyche

‘There is a distinct ontological dimension to making,’ writes the cultural theorist Ulrich Lehmann, who teaches design at the New School in New York City, ‘as it implies the emergence of the new, of something that is whole, from separate, often disjunctive and opposing components.’

What’s more, what begins in the home or classroom expands beyond familiar borders to fundamentally reshape norms around gender, capitalism, sustainability and nationalism….

Handcraft classes in schools might potentially mesh the practical with the philosophical: the knowledge of making with its civic applications – which is a matter not just of material output but of values. This is especially apparent in considering how and why people bring their handcraft into the public sphere (such as face coverings and masks) as a solution to a social ill, in the form of a sale, gift, barter or an act of community beneficence.

With making, creators live in the moment, and have – as David Gauntlett, a media theorist at Ryerson University in Toronto, writes – ‘the sense of being alive within the process; and the engagement with ideas, learning and knowledge which come not before or after but within the practice of making.’

With students likely to return to the classroom in a drastically altered schoolscape, now is the time to reconfigure the pathways to knowledge and knowing. Let mandatory handcraft courses help knit together a new route towards sustainability, equity, health and civic engagement in a post-pandemic world.

At the same time, they can offer an antidote to our purchase-driven, 24/7 culture, bringing joy, calm and flow into formalised school settings a few times a week – what the educator Ellen Dissanayake calls ‘joie de faire’.