Facing the planetary limits, what do we actually need to possess? To keep, discard, or not desire? Here’s two approaches

“Imagine no possessions/I wonder if you can/No need for greed or hunger/A brotherhood of man”. The third verse of John Lennon’s great anthem is all too evocative - and for the notoriously Rolls-Royce-bothering ex-Beatle, all too provocative. But in terms of the behaviour and lifestyle changes that zero-carbon societies require, the question of how many possessions - and what quality of possessions - each of us needs becomes absolutely essential to meet our planetary targets.

So many major forces and policies are immediately implicated here. Advertising as an engine of inciting desire for every more psychologically and socially tailored material products. Austerity as it constrains poorer families’ spending power, opening up divides in schools and workplaces between those with access to certain status goods, and those not.

But one way to focus the discussion may centre on the “possessive” element of possessions. What are the items we might want to be well-made enough, or enduring enough, or useful enough, that we might want to hang on to them beyond the usual journey to the trash bin?

And how might we be able to make those discriminating decisions, in a way that recognises that there are vast inequalities evident in the “possessions” we own, or value?

This week we came upon two voices - a photographer/ethnographer from advertising, and an professor of developmental psychology - which could help us all get a handle on our possessions.

In the online ideas magazine Aeon, developmental psychologist Bruce Hood writes about how deep into our evolved psychology our relationship with possessions goes. He begins with this incredible anecdote

In 1859, around 450 passengers on the Royal Charter, returning from the Australian goldmines to Liverpool, drowned when the steam clipper was shipwrecked off the north coast of Wales. What makes this tragic loss of life remarkable among countless other maritime disasters was that many of those on board were weighed down by the gold in their money belts that they just wouldn’t abandon so close to home.

Humans have a particularly strong and, at times, irrational obsession with possessions. Every year, car owners are killed or seriously injured in their attempts to stop the theft of their vehicles – a choice that few would make in the cold light of day. It’s as if there is a demon in our minds that compels us to fret over the stuff we own, and make risky lifestyle choices in the pursuit of material wealth. I think we are possessed.

More precisely, Hood thinks we are in the grip of evolution. One way for males to non-violently compete for mating rights with females is to put on an extravagant display in their feathers or markings - it shows their genes are strong enough that they can waste expenditure on such unnecessaries. Human beings can do this through technology:

The wealthiest among us are more likely to live longer, sire more offspring and be better prepared to weather the adversities that life can throw at us. We are attracted to wealth. Frustrated drivers are more likely to honk their car horn at an old banger than at an expensive sportscar, and people who wear the trappings of wealth in the form of branded luxury clothing are more likely to be treated more favourably by others, as well as to attract mates.

On the basis of this kind of research, the marketeers get to work. Hood tells us about the “extended self” concept decides by the marketing expert Russell Belk. In 1989, Belk claimed that:

we use ownership and possessions from an early age as a means of forming identity and establishing status. Maybe this is why ‘Mine!’ is one of the common words used by toddlers, and more than 80 per cent of conflicts in nurseries and playgrounds are over the possession of toys.

All of this sounds like we are permanently susceptible to consumerism - which in terms of the toxic material throughput of our lives, isn’t good news.

But maybe there’s a way to see the amount of possessions in our lives, map this, and be able to make distinctions about what we do and don’t need - and what we want to be robust/reusable or disposable?

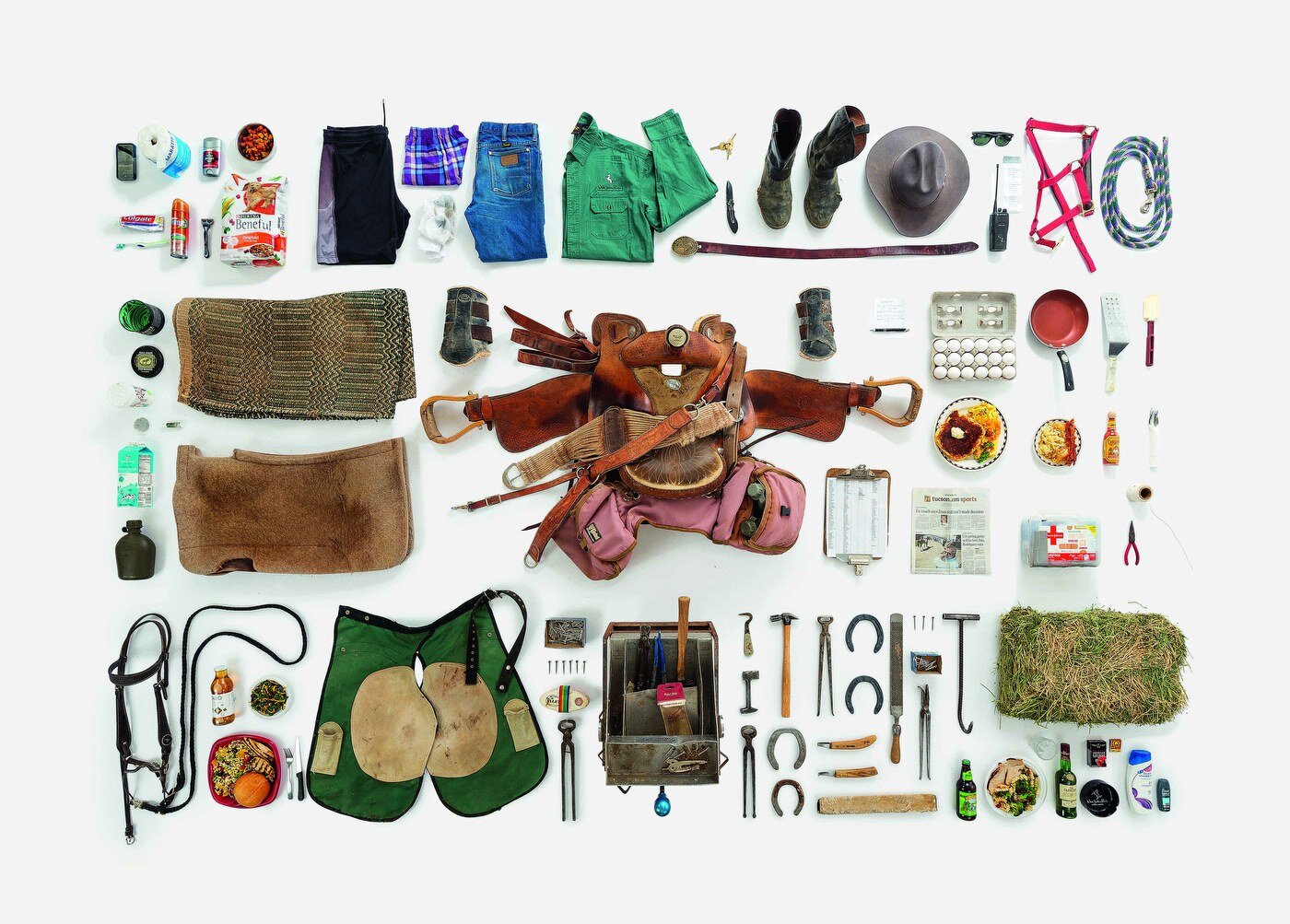

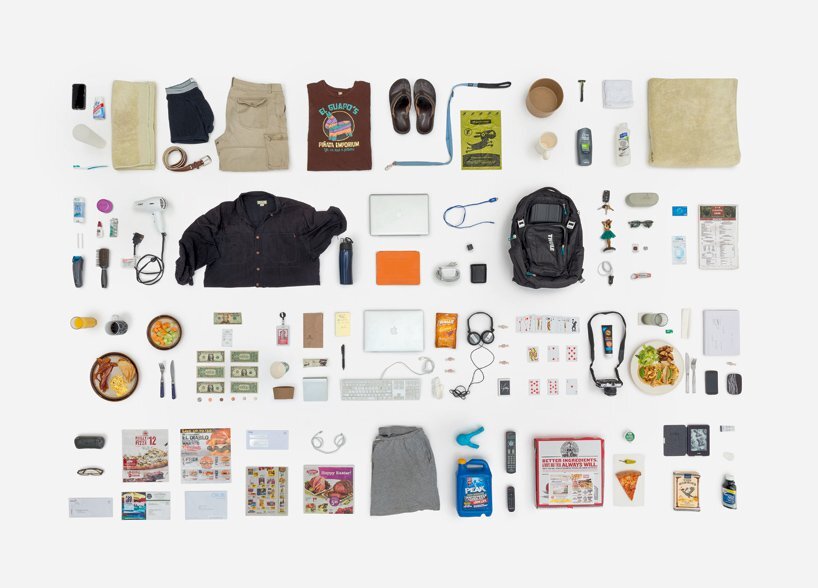

This week we heard a presentation at the New Breed #ThinkSprint at the Wellcome Institute from the ethnographer, photographer and corporate style-hunter Paula Zuccotti. Her big idea (actually launched in 2015) was called Every Thing We Touch - a simple but brilliant idea: to itemise every portable object that someone touches in their day, lay it out in sequences, and photograph it from above.

At the event Paula showed us a few fascinating slides - her work is widely available online, so here’s a selection. The first picture is that of Davis, a 29 year old violinist in Seattle The second is of Sonia, 32 years old living in London. The third is a 2 year old in Tokyo - at the stage in her development where she’s touching compulsively. is The fourth is a nun in Madrid living a rigorously austere life…. you get the point.

It’s easy to imagine this as a form of audit for an individual - a way to pick our the essential from the inessential; to identify what disposables could be replaced by reusables and repairable; to note the consumer tastes that one is aware, and unaware of; to identify the beloved objects, the ones invested with huge emotion - and also those that are cheap in their payoffs and thrills.

Indeed, this is what the Marie Kondo tidying phenomenon promises - as you can see from its “About” text;

Most tidying methods advocate a room-by-room or little-by-little approach, which doom you to pick away at your piles of stuff forever.

The KonMari Method™ encourages tidying by category – not by location – beginning with clothes, then moving on to books, papers, komono (miscellaneous items), and, finally, sentimental items. Keep only those things that speak to the heart, and discard items that no longer spark joy. Thank them for their service – then let them go.

People around the world have been drawn to this philosophy not only due to its effectiveness, but also because it places great importance on being mindful, introspective and forward-looking.

Could this method be joined to a zero-carbon-conscious post-consumerism - where having identified the most beloved and joyful objects, one only buys in ways that sustain that spark? Could we cultivate a culture where we have much less possessions in our lives, but much more unique stories to tell about those we show to the world?