Alternative Editorial: Next Level Democracy

This morning we are reading about Hong Kong’s decision to suspend a controversial law that would allow extradition of its citizens to China for trial. The decision came after a week of huge cross-generational protest, that caught the attention of the international media.

This was not a simple, knee-jerk reaction on either side – large power versus small one - but the playing out of a complex set of narratives. It included China’s own anxiety about China and Chinese culture in the world, as well as Hong Kong’s fear for its future as an attractive place for international investment. Both are soft power issues that suggested shared interests, rather than contests of might.

One notable sub-protest came from HK Mothers (pictured in this report, and themselves conflicted with past and future identities). They asked the Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, to keep HK unique. They argue that their children have grown up with an important role: ethnically Chinese themselves, but maintaining an autonomous relationship with China.

They pleaded: Don’t oblige them to seek their freedom - or even their internationalism - elsewhere. An emotional demand, but one that sought to illustrate how the mighty HK economy that China benefits from could easily collapse, if there is a loss of commitment and loyalty from the next generation.

How many of these kinds of street protests have we witnessed this year? It seems increasingly regular. As I write, we are witnessing the Sudanese protest against military rule, the ongoing protest against carbon taxes in France (now into its sixth month), the latest protest against air pollutions by Extinction Rebellion.

Hong Kong march June 2019

In this age of democratic deficit, coupled with a growing sense of personal and group agency, taking to the streets is often the only way to vent dissent or frustration. Not simply to get the attention of your local government but - in increasingly sophisticated ways - to get the attention of the world media. So that international reputation becomes another tool for change.

But how much depends upon the ability of the news media to frame the event in the interest of one agenda over another? Probably the most noticeable news battles going on right now are between those for and against US President Trump: when (maybe) 150,000 people came out to protest against his visit to the UK, he dismissed it as ‘fake news’.

In a move that may even have tested his own followers, he suggested that people came out on the streets to welcome him – so great is the love of British people for their fellow Americans. Even when people come out in unprecedented numbers, it’s too easy for the media – too often hiding their own clear agenda – to decisively shape the message.

As we have said many times on these pages, when we look at the continuing frustration of ‘the people’ to have their say, it’s inaccurate to call it a ‘loss-of-democracy crisis’. You can’t really lose something you have only poorly had. Even in the most self-declared sophisticated of democracies, no one has more than a single vote every five years.

The best we have delivered to date is the idea of one person representing the very diverse views within a constituency. That person - and the government which results from that - is routinely elected by not much more than 30% of those who decide to vote. As William Davies notes in the LRB this week, the collective illusion that such a system – or “theatre”, as he puts it - is democracy, has kept us all in its thrall for too long.

As we write, many experiments for an improved democracy are underway – many of them digital. As we’ve reported before the search for an ideal democracy platform has been on for some time and remains, for now, the Holy Grail.

Something that’s able to catch more than crudely framed ideas for simple yes/no responses, allowing something that feels more deliberative, is still out of reach. But it has been very close for some time – check (ref all) the Common Platform, Open2019, Holochain, Loomio, DoItLife, Global Vote.

Can the digital help us get beyond “entry-level democracy”?

Earlier this week we attended a very useful event called Digital Democracy in Question at Kings College, London which offered a mixed review of how far we are in this pursuit. What became clear is that there are two strands of development that overlap but should not be conflated.

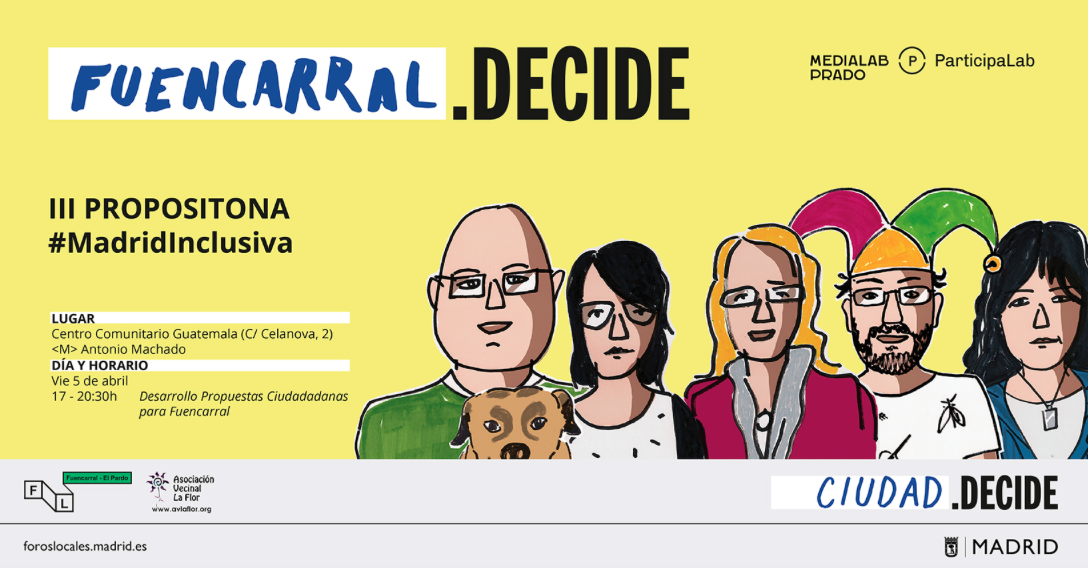

Yago Bermejo Abati (Media Lab Prado) told a heart-warming story about Decide Madrid which has already elicited 26,000 citizen proposals, which are regularly processed through clustering, leading to collaboration amongst citizens - which results in city-level innovation.

In addition Madrid has its own version of Citizens Assembly known as City Observatory – sortition-led decision making. Imagine waking up with an idea about how to improve your community and having somewhere to go to make that happen.

Iceland’s Pirate Party

However, another speaker - Ásta Helgadóttir (Former Iceland Pirate Party MP) -described the less successful experiment of the Icelandic Constitutional Assembly (ref). Proclaimed as the chance for citizens to take part in the re-design of Icelandic governance, the new model was never implemented. This led ultimately to a loss rather than an increase of trust in political agency.

The Pirate Party’s own experimentation throughout that period with liquid democracy – digital voting with the option of transferring your vote to an expert (ref) – was short lived, reported Ásta. Once they had set up their digital platform, everyone arrived with their personal, rather than agreed, agendas.

Asta described poor user interfaces that could not capture the will of the people. This also occasionally led to the escalation of conflict rather than resolution.

There were no safety measures against those with the most time and energy engineering the results they wanted.

“If you have 1000 people signed up, but only 100 are actively participating in decision making, is that democratic?”, she asked. Maybe not. Or is it a necessary discomfort while we are in transition to a better system, getting more used to participating?

A good question arises here. In designing our own digital websites for the future, should we take care to keep broader policy agendas, or ideological debates, separate from projects aimed at building up participation? That may sound like an impossible distinction. But in our climate window, is it necessary? How important is the idea of subsidiarity – that is, ensuring that decision making occurs as close as possible to the people who are affected? [In passing, we wonder what the link might be between subsidiarity as a concept and anarchist traditions?]

But will digital democracy deliver what is really intended by the bigger dreams of democracy which must surely mean some kind of shared ownership of the future? Some felt and enabled agency for every individual, in the shaping of their own life? For that we would need so much more than a chance to vote on someone else’s ideas.

Especially if that person, due to vastly different experiences in life, can barely recognise your picture of reality. And what if that reality wants to shut down the time to deliberate the issues that face us? As Audrey Tang says, voting is just “entry-level democracy”.

For that we need something more complex, at the level of a deepened and enhanced democratic culture. And that can’t simply be “switched on”. Indeed, we are trying to move away from the instrumentalization of the vast majority of people in the maintenance of a growth economy that has destroyed our planet.

So we must expect that many, maybe most people will not have the time, space or attention available for participation, at the level which we – the usual suspects in this democracy quest – feel is needed. How do we prepare the ground?

When the conditions are right, then the (digital) tools become relevant

First we have to start with a basic inclusion in society. We need to create spaces where any kind of person can enter into a connection with someone they wouldn’t otherwise meet and have a conversation (see our earlier editorial). That’s not one kind of space but all kinds of spaces, appealing to a modern and diverse population that expresses their preferences in so many ways.

Role of empathy in democracy

To make that chemistry happen, those spaces must be attractive – not demanding. We’re thinking more festivals and circuses than debating societies. And within those spaces, there should be a wide variety of different speeds of entry – from board games to listening circles to innovation labs. Whatever it takes to make relationship happen more authentically: not predetermined by the 2% political agenda.

And then out of those growing relationships, trust grows. With trust comes the possibility of collaboration and mutual decision-making – the fabric of community flourishing. Into this fertile ground, all the preceding democracy processes can be planted and thrive - from People’s Assemblies to on-line digital voting. But without those in-person, viscerally-felt relationships as a foundation, new democratic mechanisms can be as alienating as the current system.

If this is a patient, evolving process, are we condemning ourselves by going too slow? Not really: in the right conditions – a festival, a shared happy or sad experience, the impact of a piece of art (eg the 2012 Olympic Opening Ceremony), a march – these relationships can build very quickly. It’s the depth more than the amount of time that counts. We are developing exactly these kinds of shared entry points as part of our collaboratory ‘Friendly’ events.

From the limited success we have already had – examples here from Plymouth and Kings Cross - it’s in those moments of being deeply together, without an overly articulated purpose, that something inside us wakes up. Parts of us come together that have been fractured for most of our waking lives. We are suddenly ready to do things differently.

How many saw the documentary on the making of the 2012 Olympic Ceremony? Where people had been brought together - against all the odds – by the vision of a multi-cultural, post-Imperial Britain. Not a single person’s achievement, but a collective spectacle, patiently co-created with a volunteers, including local people living in the shadow of the Olympic village.

In an interview with the scriptwriter Frank Cottrell Boyce soon after, he confessed a disappointment that not more had been made of that moment – as a springboard for healing some of the divisions in our society. Instead, as we have seen, politicians have harnessed those complexly patriotic emotions, mobilised them behind crude slogans and only deepened wounds.

But history has shown that there is always a moment when disaster could have been avoided - if enough people wake up to the reality of not only their own situation, but to the dangers we face collectively. Maybe in 2012, post-Ceremony, the solutions and mechanisms that were needed to deliver the voices of the people – to bring communities together, to turn the climate catastrophe around – were not available. Or not known.

But after two years of blogging on the Daily Alternative, we know that, in 2019, they most certainly are. Let’s be sure to use every tool in the box, to now make this happen.

Decide Madrid