Is creativity, not money, the key to happiness? Only partly. Csikszentmihalyi's "flow" revisited

It's an arresting title (and blog). You may have heard of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (that's pronounced "chick-sent-me-high") and his psychological concept of flow - defined here:

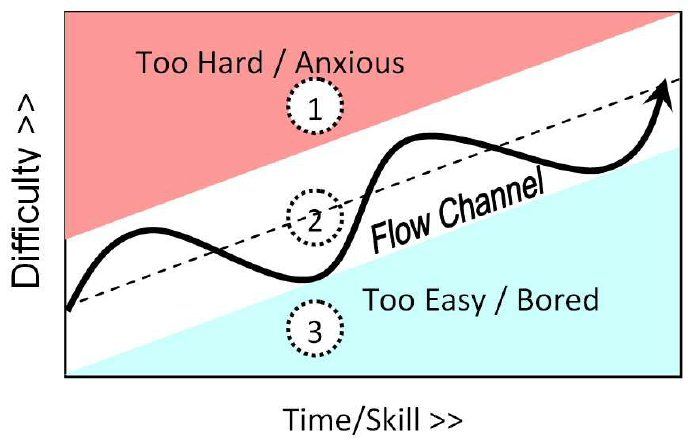

Also known colloquially as being in the zone, flow is the mental state of operation in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity. In essence, flow is characterized by complete absorption in what one does, and a resulting loss in one's sense of space and time.

The concept is over forty years old (coined in 1975), and has gone through the full cycle of being celebrated, then normalised, and then critiqued. The Wikipedia entry contains the nub of the critique - that the flow state (originally modelled on peak performers like sportspeople or musicians) can become addictive. "At which point [says Csikszentmihalyi] the self becomes captive of a certain kind of order, and is then unwilling to cope with the ambiguities of life."

The downside of "flow" sounds like it might well describe much of our current engagement with social media and games. Those moments we lift our heads from the smartphone, lost in our chosen loops and bubbles of content, wondering where the time has gone. Or for those "captive of a certain kind of order", what about the regularly reported epidemics (here and here) of young men simply staying at home playing in their game worlds, retreating from the challenges of employment or civic life with others?

What this excellent Open Culture blog post reminds us of, however, is the original historical and biographical context of Csikszentmihalyi's research:

After living through the Second World War in Europe (he grew up in what is now Croatia), Csikszentmihalyi says he “realized how few of the grownups I knew were able to withstand the tragedies that were visited upon them; how few of them could even resemble a normal, contented, satisfied, happy life once their job, their home, their security was destroyed by the war.” He became interested, he says, “in understanding what contributed to a life that was worth living.”

The Open Culture blog goes on to make some interesting Buddhist parallels:

We naturally experience the greatest happiness when fully absorbed in work we find meaningful and fulfilling. What Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow” is a meditative state we might compare to the ancient Buddhist state of ekaggata---or “one-pointed concentration”---a state meditation teacher Shaila Catherine describes as“certainty, deep stability, and clarity…. The mind is completely unified and ‘one with the experience.’” Indeed, like the Buddhist conception, which contrasts ekaggata with a restless greed that can never be satisfied, Csikszentmihalyi contrasts “flow” with wealth, and cites research suggesting that above a certain level of basic material well-being (which far too many people do not yet have), “increases in material resources do not increase happiness.”

This last point is a truism of the new wellbeing economics that we have profiled strongly here. Yet the story that can convince everyone, trapped in the current business model of work-to-consume, that their relationships (and their own passionate pursuits) are what provide most of life's satisfaction, is not yet being properly and compellingly told - at least beyond certain intentional cultures (spiritual, feminist, activist).

If "flow", these days, feels like it might have been captured by the great desire machines of contemporary capitalism - "Netflix and chill", as they say - then what are the mood-states that can help us repossess our selves, or can jolt (or bliss) us out of our routines? Would being shocked, or addressed at a more primary emotional level, be the inner explosion that would helps us see the moorings which have held us?

This presentation made by A/UK at the Innocracy conference in Berlin is a pointer to the kind of questions we're asking (and the sources we're sampling) about emotional literacy and political/civic life.

In short, it may not be enough to aspire to be "in the zone", according to Csikszentmihalyi - there is a greater symphony of "given" needs that may have to be played, in order to fuel a healthy and flourishing self in society.

More from the Open Culture blog here.